The original Final Fantasy on the NES is the best game in the series. I'd go so far as to say that—while no game is perfect—Final Fantasy is marred by only a single solitary flaw.

It should be noted that I have no significant nostalgia for this game which might tint my glasses rose. I read a lot of 8-Bit Theater when I was 14, but the first game from the series I played was 7, followed by 6, Tactics, 8, 4, and 10. I lost interest when I learned 11 would be an MMORPG. So while my judgment cannot reasonably be criticized for being poisoned by nostalgia, I could justifiably be called out for not having played enough of the games to make any claim about which is GOATed. Luckily this website has no comment section for pedantic quibblers to ply their noisome trade in. I can do whatever I want.

In late 2022 my partner Morrie and I decided it'd be fun to play through each of the first 10 numbered Final Fantasy games in order. We opted to begin with the 1987 NES release rather than playing any of the various updated versions because the appeal of playing through the whole series in order is to see how the games evolved over time. Getting that perspective requires sticking as close to the original formats as is reasonable. Prior to this I'd dabbled with the first game. I've knocked Garland down probably half a dozen times over the years, and got as far as the Marsh Cave maybe once. Playing together with Morrie is the first time I've taken the game seriously. Having now slain Chaos and closed the 2000 year time loop I am prepared to render judgment.

Every element of this game exists intentionally. The series that sprang from it is mechanically pretty loose. Collections of cool ideas thrown together without much regard for how they cohere into a whole. I've never had trouble getting through a Final Fantasy game while ignoring 90% of the spells, items, and character abilities. Random encounters were just padding that must be endured in order to gain enough xp for the next fight with emotional stakes. The compelling part of these games is the written narrative. The mechanics are just a vehicle for moving the characters through that story, usually with a few novel systems (often with plot relevance) bolted on top of the basics for flair.

Later games in the series are stories told through the medium of a video game. This isn't a damning flaw, but in contrast Final Fantasy is a game qua game. Learning to overcome its challenges feels paramount to the experience. The moment-to-moment gameplay functions in support of the sparsely written narrative by guiding the players to think about the world as characters living in it do.

Final Fantasy is a game about calculated risk. Players begin in the safety of a town where, if they want, they could spend their play time walking back and forth saying townsperson dialogue anytime they bumped into someone. Instead they will choose to venture away from safety into the distant places where great deeds can be accomplished. Each step they take away from town increases their risk because it is one more step the player will need too retrace to return to safety. Saving and healing are not, at first, available at all outside of town; and later are available as limited resources which can be replenished only in town. Random encounters deplete resources at an unpredictable rate. Thus moving away from town puts the player in a constant state of attrition. If they miscalculate their risk and venture further than they're able to handle they will be killed and all the gold and experience they've gained will be lost.

The primary skill Final Fantasy tests is memorization. By learning the patterns of this fantasy world—its geography and biology—the player is able to calculate the risks they take more accurately. This is far more relevant to success than the gradual increase of the party's vital statistics, which occurs largely in the background and doesn't influence the player's decisions outside of periodically making new spells available for them to choose between.

Each time the player reaches a new town the gameplay that follows takes a similar form. They begin by meandering aimlessly through the surrounding landscape looking for anything unusual that might be worth exploring. As they wander their company encounters monsters at unpredictable intervals. Their resources erode: they have fewer hit points, healing items, and spells than they did when they set out. In exchange they've gained some gold and some experience points, but these only represent the potential for greater resources in the future. The player will need them later. They're worth accumulating. But you can't heal yourself by rubbing gold on your wounds.

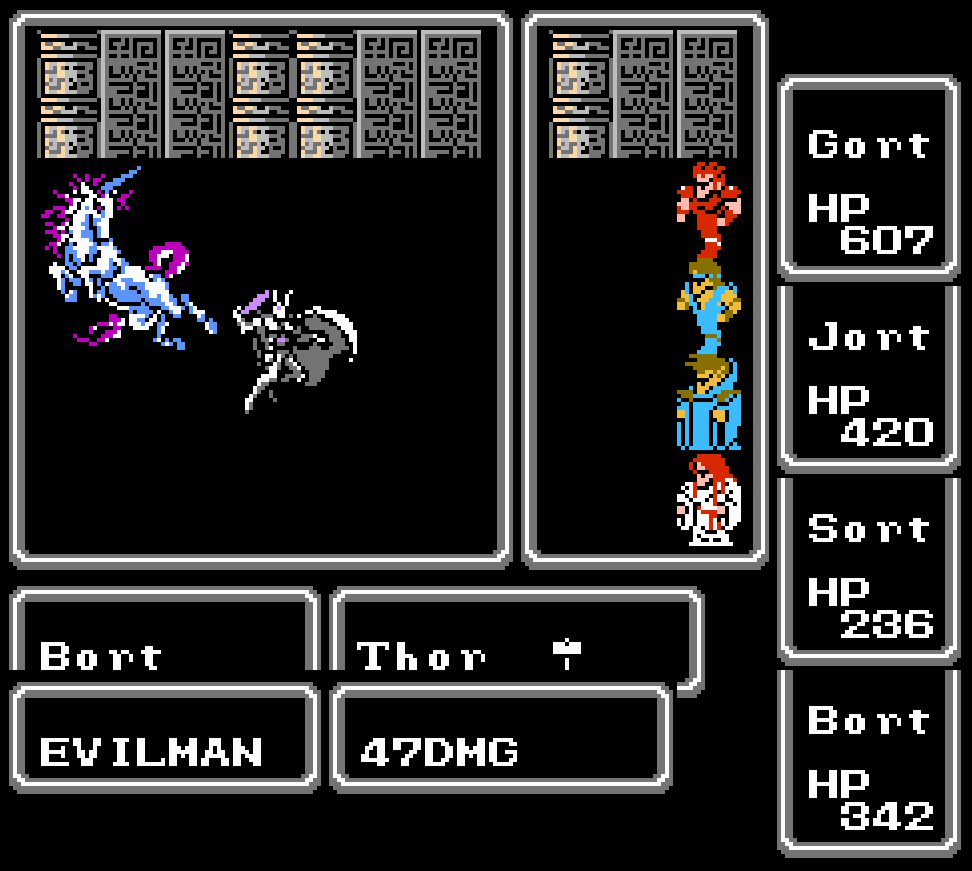

The player spots a cave entrance in a range of mountains and enters it. They're presented with multiple directions they can explore in. They run into some dead ends, open some treasure chests, and eventually find a staircase to take them to the next level. While they do all of this they're encountering new sets of monsters, different from those they're used to fighting in the overworld. They look tough, so the player focuses all their attacks against one foe at a time. The window displaying the results of each event within the combat lingers on screen, allowing the player to take mental note of which spells do better or worse than they expect; as well as keeping a rough tally of how much damage each monster takes before it is terminated. Some monsters aren't as tough as they looked, and some of the party members waste their actions because they were directed to attack a creature that has already been killed.

By the time the player's company of Light Warriors has made it down a few flights of stairs they've taken quite a bit of damage. They're down to their last few HEALs, and have spent most of their spells. They decide to finish exploring this level before they leave, but when they find the stairs it's tempting peek at what's ahead. They descend, and find a chest just a few paces away. Halfway to it they have an encounter with a monster new to this level. One of their Light Warriors is slain. They survive the battle but it's clearly time to leave. They can't resist the extra risk of taking a few more steps to open that chest—luckily it isn't protected by a guaranteed encounter, as some chests are. The reduced party retreats from the dungeon back through each level one by one. They still face encounters, made more difficult now by their reduced numbers, but they make it across the overworld and back to town.

Here they can use the treasure they earned to resurrect their fallen comrade. They may also be able to acquire better spells, weapons, and armor than they had before. If they're in the early part of the game they'll buy as many healing items as they can afford; in the later part they'll buy as many as the party can hold and still have plenty of money left over. Finally it's time to rest at the inn. Their hit points and spell slots are restored, both of which may have greater maximums than the last time the player was in town due to all that experience they gained. Sleeping at an inn also saves the group's progress. Another expedition into the unknown completed successfully.

Now the player sets out again. They direct the party straight to the cave entrance then straight to each set of stairs in turn. When encounters occur they've developed a good sense of what it takes to kill each monster and are able to effectively divide the party's actions up to end fights more quickly. In a surprisingly short amount of time they've arrived back at that chest which tempted them earlier, their resources only barely depleted from what they set out with.

At the bottom of a few of these caves are big scary boss creatures with sprites that take up the whole left side of the battle screen. Morrie and I frequently began these fights feeling intimidated, only to be surprised by how quickly the bosses were defeated. The Final Fantasy series typically ends dungeons with boss battles that are challenges unto themselves. They have to be, because players are usually given the opportunity to restore their resources and save their game just before the boss fight. In Final Fantasy, though, the challenge is the uninterrupted attrition of the dungeon, and the boss is merely the dungeon's 'final form.' A test to see if you've managed your resources judiciously to the very end.

Readers familiar with my much more prominent body of writing have probably noticed the blatant similarities between Final Fantasy's game play and the style of dungeon exploration often practiced within the play culture of the OSR. It is interesting to me that this video game which is very obviously based on 1980s D&D has in some way preserved the way D&D might have been played in the 1980s. Further, that the preserved style of play is so similar to the one that was developed as a new form through the late 2000s and early 2010s; which though it drew upon the texts of the '70s and '80s was definitely not emulating those lost play styles, despite what everyone said we were doing at the time. It's also worth noting that my long association with OSR thinking colors the way I'm interpreting the game. My glasses may not be tinted rose, but they definitely have a sheen of anti-copy blue.

Morrie and I have started playing Final Fantasy II now. A fan translation so we can hew as close as possible to the original presentation. It's been fascinating to see all of the things this game is doing differently, how much more it leans into its written narrative, but also all the interesting developments in its mechanics. I can't form any opinion on it yet. Once I've played more of it I may decide that it's even better than the original, but it is a bit sad to see how being able to save anywhere on the overworld at any time has already dispelled that feeling of towns as bastions of safety from which the player ventures out on dangerous expeditions. That particular sort of adventure is unique to the first game alone.

As to that single solitary flaw I mentioned in the opening: It sucks that you can only purchase one unit of anything at a time. Anytime the party visits town they need to stock up on 99 HEALs, and that means sitting there and pressing the A button roughly 297 times in a row. That's not hyperbole I mathed that out. God help you if you're in a town where HEAL isn't the first item in the shop, so you've got to mix it up by repeating a-down-a-a 99 times. Or if you need to stock up on 99 antidotes or something. There are times when we opted to travel halfway across the world just for an item shop with a different menu layout.

—Nick LS Whelan

May 1, 2023